Most of you have probably heard of Sherlock Holmes, seen movies, and read books about him and his investigations. How many of you have seen movies about Enola Holmes? And have you paid attention to the story behind the second film? After watching the credits, I realized that the story about the matchboxes was based on a true story, and that definitely caught my attention. So, as always, I did my research and want to share some interesting facts with you.

In 1852, Charles Dickens wrote about the dangers of phossy jaw in match factories. This was long before the Bryant and May factory opened on Fairfield Road in East London. However, when the factory opened in 1861, white phosphorus was still being used there and was causing disease.

The matchgirls were in danger not only while working, but also when they had to eat in the same room, leading to osteonecrosis, otherwise known as phossy jaw, which was a form of bone cancer.

Phosphorus necrosis of the jaw, commonly called ’’phossy jaw’’, was indeed a dreadful disease and overwhelmingly a disease of the poor. Match factory workers had insufferable abscesses in their mouths, resulting in facial disfigurement and sometimes fatal brain damage.

On June 15, 1888, the Fabian Society held a meeting at which social reformer Clementine Black spoke about the situation of women’s labor at the time, and Henry Hyde Champion stated that Bryant and May was receiving over 20% in dividends for its shareholders while paying its workers ’’starvation wages’’.

The next day Annie Besant (also a Fabian) and Herbert Burroughs approached Bryant and May workers at the factory gate, where they questioned the Matchgirls about their work experiences. The girls complained of poor working conditions, fines, low wages, and the risk of getting a phossy jaw.

Besant published an article, ’’White Slavery in London’’ in the magazine ’’Link’’, that she ran:

Annie Besant was threatened to be sued by the Bryant and May, and their female employees were required to sign that the article was untrue. The girls refused and wrote a letter to Annie Besant:

On July 5, 1888, 1,400 women went on strike. The day after the strike, about 200 women marched to talk to Annie Besant. A deputation of three (Mrs. Mary Nauls, Mrs. Mary Cummings, and Sarah Chapman) was invited to see her, and although she did not agree with the strike, Besant agreed to help them.

The London Workers’ Council and the strike committee met with the Bryant & May directors on July 17. All of their demands were met, and terms were agreed to in principle:

all fines to be waived;

all deductions for paint, brushes, stamps, etc. must be discontinued;

all claims must be made directly to the firm before any hostile action is taken;

all girls must be taken back.

It was also agreed that the girls would be given room to eat.

After a while, the name of the union was changed to ’’The Matchmaker’s Union’’ and both men and women were accepted. Sarah Chapman became the first elected TUC representative from the newly formed union.

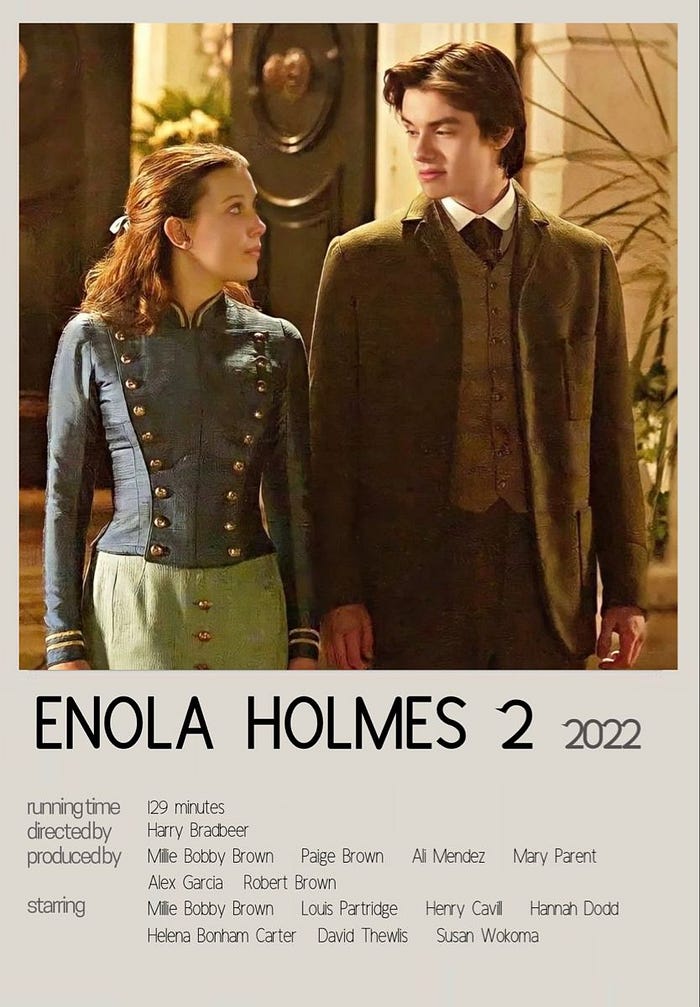

Now that we know the real story of Enola Holmes’ case, what really happens in ’’Enola Holmes 2’’?

Enola got her first case, and she needed to find a missing person, which turned out to be Sarah Chapman. Sarah worked at the Lyon match factory, had her own life, and then she completely disappeared from everyone’s lives. What or who is behind it all?

Enola discovers that Sarah disappeared after ripping out several important pages from books at the factory. Those pages contained evidence of the factory’s wrongdoing. They were using cheap white phosphorus, which was poisoning the employees and causing them to get typhus.

Movies and books are what help us learn more about anything. Even though it was only a movie, I learned some interesting historical facts through it.

It is true that who we are is determined by the books we read, what we watch, and who we surround ourselves with.